This page is about Andy Bristol, my best friend and former boyfriend.

This page is about Andy Bristol, my best friend and former boyfriend.

This page is about Andy Bristol, my best friend and former boyfriend.

This page is about Andy Bristol, my best friend and former boyfriend.

Andrew Strawn Bristol is the survivor of a bleeding brain aneurysm and stroke. He's currently living with his father and step-mother in Georgia, where he gets the ongoing supervision and care he now needs due to his mental deficits. He's physically independent and his personality is intact, but his concentration and short-term memory are very minimal. This will probably be true for rest of his life.

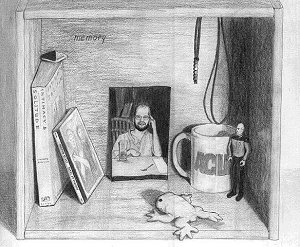

This page started out as a place for "live" updates about his condition. As his situation stabilised, the page evolved into a more thorough account of his stroke and recovery. If that's the only part you're interested in (which I understand; it's the kind of information I was frantic to read when this first happened to Andy), you can jump to it. But this page didn't say much about Andy himself, which has come to bother me. Especially since he'll probably never be able to put together a personal web page of his own, I've decided to take a stab at it. It's rather incomplete because I don't know his whole life story (having missed the first two decades of it, and now the past several years of it), and because some of it is simply too private, and I may get parts of it wrong because it's second-hand information. But I want to tell you about the man who means more to me than anyone.

Growing Up

Andy was born in Minot, North Dakota on 11 June 1969. He says that it was a great place to spend the first year of his life: before he developed any permanent memories. {grin} His father William ("Bill") was a physician there; his mother Carol cared for Andy, his brother Steve, and sister Shelly. They moved to Kalamazoo, in southwest Michigan.

Andy was born in Minot, North Dakota on 11 June 1969. He says that it was a great place to spend the first year of his life: before he developed any permanent memories. {grin} His father William ("Bill") was a physician there; his mother Carol cared for Andy, his brother Steve, and sister Shelly. They moved to Kalamazoo, in southwest Michigan.

His parents divorced when he was fairly young. Knowing them now, their separation makes perfect sense. It's not that they hate each other (they seem to have a cordial relationship); they were just a poor match. Especially when I consider how very different Bill's second wife Jacoba ("Coby") is from Carol (an observation that both of them would probably take as a compliment), and how much Bill seems to appreciate Coby's nature, I can see why he and Carol weren't happy together.

After the divorce, Andy lived with his mother. He's mentioned living with his father and step-mother for a while, but said only that it didn't work out. Andy is definitely his mother's son, so he probably didn't fit well with his father's new family any more than she would have. His sister also lived with Andy and his mother; his brother lived with his father. At some point, his father, step-mother, and brother moved to St. Simons Island, located in the network of islands and narrow waterways along the coast of Georgia. And so the family split into the Michigan Bristols (whom I saw fairly often and got to know during my relationship with Andy) and the Georgia Bristols (whom I saw only a few times before the stroke). They all stayed in contact, but there was clearly some emotional distance, either as a result or just exacerbated by the physical distance.

After the divorce, Andy lived with his mother. He's mentioned living with his father and step-mother for a while, but said only that it didn't work out. Andy is definitely his mother's son, so he probably didn't fit well with his father's new family any more than she would have. His sister also lived with Andy and his mother; his brother lived with his father. At some point, his father, step-mother, and brother moved to St. Simons Island, located in the network of islands and narrow waterways along the coast of Georgia. And so the family split into the Michigan Bristols (whom I saw fairly often and got to know during my relationship with Andy) and the Georgia Bristols (whom I saw only a few times before the stroke). They all stayed in contact, but there was clearly some emotional distance, either as a result or just exacerbated by the physical distance.

Andy is bisexual, and he came out at a fairly early age, especially by the standards of the 1980's. His mother drove him to a lesbian/gay support group at the local university because he didn't have his driver's licence yet. So although I'm 4+ years older than he, he'd been "out" longer than I, a fact which frequently balanced out our elder/junior relationship, especially early on. His mother was very accepting of Andy's difference, and even became a regular at Phoenix Church, a non-doctrinaire Christian congregation formed as a haven for gay and lesbian people. As for his father and step-mother, he recounted sardonically a comment she had made (paraphrased here): "There's no one more accepting of gay people than your father and me, but we wish you wouldn't be so political about it." She has a family member who is lesbian, and she's definitely not anti-gay... but she apparently didn't grasp that to Andy, being openly-gay during the Reagan administration was like being "openly black" during the Eisenhower administration. There was no escaping the politics of it.

I can't begin to do justice to telling about Andy's friends and social life during this time. Over the years we were boyfriends, I got to know a few of his schooltime friends, but since I was never more than a frequent visitor in Kalamazoo (I lived about an hour a way, so it was mostly day-trips), his friends never really became my friends. Not that there was any major friction between us... we just never got the chance. I consider myself pretty open-minded and liberal (by that time I was an official Gay Activist, after all), but they weren't the sort of people I would've gotten to really know on my own: anarchists, hardcore libertarians, pagans, radicals, and self-described freaks. I say that not to judge or criticise them - quite the contrary - but as an acknowledgement of my own limitations. I could tell that (to mention three of the most prominent ones) Cat, Ian, and Michael were people who meant a lot to Andy, and that fact helped me to see what he saw in them. And on the other side of the coin, I never felt anything but warmth and acceptance from them, despite my being such an uptight, left-brained, suburban-upper-class, stick-in-the-mud moderate. I wish I'd taken better advantage of the opportunity to grow that they offered me.

Our Time Together

Andy and I met at the 1989 "gay pride" event in Grand Rapids, Michigan, the day before his 20th birthday. As the state's second-largest city and a community quite different from Detroit (in both good ways and bad), GR is the unofficial capital of West Michigan. So it happened that GR had the first publicised Gay Pride event in the area, and people from Kalamazoo and other cities in the area came to the event. At the time, I lived in the smallish city of Holland (where I'd gone to college, half an hour from GR), but my job, family, and roots were all in the city. I was a senior member/junior leader of Windfire, GR's lesbian/gay youth group. Still high on the excitement of coming out in the preceding year (to anyone who was paying attention, and then some), I overcame my natural shyness and got up on stage to talk briefly about Windfire. I guess this impressed Andy (who'd already been out for a few years by that time and was already an outspoken activist), and who knows what else he saw in me, so he started driving to GR for the group's Thursday evening meetings... partly to get ideas for how to start a similar group in K'zoo (his official reason), partly to get to know me better.

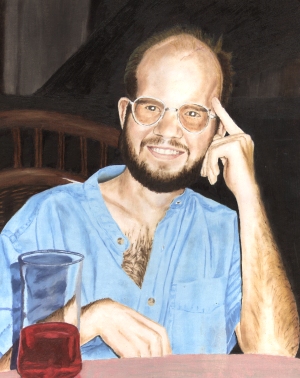

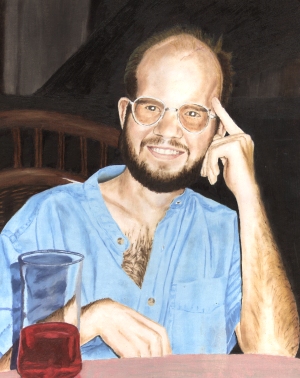

The K'zoo youth group didn't happen (not until a few years later), but he succeeded with the other goal. I thought he was cute, I appreciated his intelligence, and I thought he was funny. I've never been a fan of beards and he was kind of short, and not exactly a hunk, but I didn't hold that against him. Plus, he was interested in me! (A factor not to be discounted when talking about a young adult male who's spent his whole life surrounded by guys who were only interested in girls, and who is thoroughly uncomfortable approaching other people.) In the parking lot at Burger King (where the Windfire gang usually went to hang out after meetings), he gave me his phone number and asked me to call him. I still have that scrap of paper.

Our first real "date" was on the 3rd of July, which we later considered our anniversary date... both because the calendar date was fairly memorable, and because the date itself was. Andy took the first step (like he did with most things between us), and suggested that we meet in downtown GR (near "our" BK) after I got out of work that day. We just walked around downtown, with me showing him the sites of interest (which didn't take long {smile}). And we talked. We discussed religion (he believes in Christianity, but doesn't regard the Bible as the first and last word on everything, so he also believes in earlier and more recent wisdom such as that of Paganism or Humanism), politics (he's supportive of the Democrats, but prefers the Green Party, and deep down he's a Constitutional Libertarian), family (see the info above), sexuality (he's bi, but said he was in danger of losing his "credentials" because he hadn't had sex with a woman in so long), etc. Andy had a throat infection that day, and he's always taken the concept of "safe sex" very seriously, so we didn't actually kiss. Instead, at the end of the date we sat in his brown AMC Eagle in the library parking lot, and had the most intense hand-holding session I've ever experienced, with each of us exploring the other's hand with our own. Technically it wasn't sexual (which is why technical definitions of "sex" are so worthless), but it was incredibly sensual.

We continued seeing each other like that (but also kissing, after the infection went away {grin}), generally taking turns driving to the other's city, and getting to know each other. After a while, I invited him home... which was a big step not because of the romantic implications of that, but because I was living in a house with several of my fraternity brothers from college at the time. They'd already dealt with the fact that I was gay and were OK with it, and my dear friend Carl (the guy whose name was on the lease) was always vocally supportive of me, so the visit went smoothly. Shortly after that, Andy invited me to his home. Visiting him was sometimes a bit awkward, because he still lived with his mother, and her house is pretty small. She did her best to stay out of our way, but I inevitably got to know her (and the cats) in the process of my time spent visiting Andy. (Andy didn't get to know my family as well, simply because I didn't spend as much time with them as he did with his. Another regret of mine. But he was always welcomed by my family, and joined me for a few holiday gatherings.)

We continued seeing each other like that (but also kissing, after the infection went away {grin}), generally taking turns driving to the other's city, and getting to know each other. After a while, I invited him home... which was a big step not because of the romantic implications of that, but because I was living in a house with several of my fraternity brothers from college at the time. They'd already dealt with the fact that I was gay and were OK with it, and my dear friend Carl (the guy whose name was on the lease) was always vocally supportive of me, so the visit went smoothly. Shortly after that, Andy invited me to his home. Visiting him was sometimes a bit awkward, because he still lived with his mother, and her house is pretty small. She did her best to stay out of our way, but I inevitably got to know her (and the cats) in the process of my time spent visiting Andy. (Andy didn't get to know my family as well, simply because I didn't spend as much time with them as he did with his. Another regret of mine. But he was always welcomed by my family, and joined me for a few holiday gatherings.)

We turned out to be good for each other. We liked a lot of the same kinds of music and movies and books, we enjoyed doing the same sorts of things, our political and social philosophies overlapped quite a bit (though he tended more towards Libertarianism than I), neither of us smoked or drugged (but were both tolerant of those who did), and I didn't need to worry about him understanding what I was talking about if I quoted a line from one of Shakespeare's plays... or an episode of Star Trek... or a Smiths song... or an essay by Swift. Where we differed, we usually complemented and challenged each other. For example: Andy rarely drank, which led me to drink less often. I was in better physical shape than Andy was, which encouraged him to exercise more. Fed up with the hassles of car ownership, Andy instead used his bicycle, which still inspires me to bike whenever I can and to drive less often. I'd finished college, which encouraged Andy to continue with school. Andy loved cooking and believed in good nutrition, and goaded me to resort less often to fast food and frozen meals. I was more cautious and responsible, and coached him to be more so. He was more outgoing and spontaneous, and helped me be more social and "get in touch with my id". I taught him what I could about computers. He taught me what he could about natural medicine. He encouraged me to try reading more underground comics. I showed him superhero comics that were just as good. I grew a beard (briefly). He shaved his (briefly). And we discovered some good music, movies, and books together, which is one of the joys of being in a relationship. I think we both were better people when we were together. I know I was.

We turned out to be good for each other. We liked a lot of the same kinds of music and movies and books, we enjoyed doing the same sorts of things, our political and social philosophies overlapped quite a bit (though he tended more towards Libertarianism than I), neither of us smoked or drugged (but were both tolerant of those who did), and I didn't need to worry about him understanding what I was talking about if I quoted a line from one of Shakespeare's plays... or an episode of Star Trek... or a Smiths song... or an essay by Swift. Where we differed, we usually complemented and challenged each other. For example: Andy rarely drank, which led me to drink less often. I was in better physical shape than Andy was, which encouraged him to exercise more. Fed up with the hassles of car ownership, Andy instead used his bicycle, which still inspires me to bike whenever I can and to drive less often. I'd finished college, which encouraged Andy to continue with school. Andy loved cooking and believed in good nutrition, and goaded me to resort less often to fast food and frozen meals. I was more cautious and responsible, and coached him to be more so. He was more outgoing and spontaneous, and helped me be more social and "get in touch with my id". I taught him what I could about computers. He taught me what he could about natural medicine. He encouraged me to try reading more underground comics. I showed him superhero comics that were just as good. I grew a beard (briefly). He shaved his (briefly). And we discovered some good music, movies, and books together, which is one of the joys of being in a relationship. I think we both were better people when we were together. I know I was.

I had a steady well-paying job that I liked, and had figured out what I wanted to do with my life (at least at the time). Andy was still working on all that. He knew he wanted to do something in health care, but had trouble getting anywhere with it. Med school was out of the question (he wasn't a particularly good student, probably due to Attention Deficit Disorder and some manageable emotional problems), but something in nursing or alternative medicine appealed to him. He did personal care work for severely disabled clients (helping on a daily basis with dressing, bathing, feeding, etc.). He tried enrolling in the nursing program at Lansing Community College, which meant moving to Lansing. Since this would have put him nearly two hours away from me, this prompted me to do something I'd been considering anyway: moving out of the house I shared with my college friends, and getting an apartment of my own in GR itself, closer to my job... and only an hour from Lansing. LCC didn't work out, though, so he moved back in with his mother... still an hour away from me to the south. A couple years later, Andy made a bigger move (taking a different angle on the health care work he wanted to do): to the east side of the state to attend a first-rate massage therapy school there. I didn't move that time (after all, I'd since taken a different job further to the west); we just accepted that we wouldn't be seeing each other as often for a while.

That was kind of typical of our relationship: we were never really "together". We'd randomly take turns driving to the other's city when we wanted to spend time together. Between visits, we'd talk on the phone. (I've always hated talking on the phone; if I'm talking with someone, I need to see them and for them to see me. But with Andy it was comfortable... though he still tended to dominate the conversation. He had the habit of starting a sentence quickly, then pausing in the middle of it to figure out how to finish. I always wait until I've formulated the whole thought before I open my mouth. Guess who usually won the "what do we talk about next" contest.) At any given time, I might be interested in "settling down together", or he might be... but not at the same time. When we first started seeing each other, the fact that we lived in different cities and saw each other infrequently made it seem only fair that we didn't consider ourselves a "couple". If I happened to be busy in GR, why shouldn't he go out to the bar in K'zoo and dance and flirt and have fun? And vice versa. He still had his friends in K'zoo and I had mine in GR, so we didn't have many of "our" friends. Which was fine, because we trusted each other. Just because we didn't see each other on a day-to-day basis didn't mean we weren't "faithful" to each other in every way that really mattered. As time went on, Andy specifically told me he didn't want our part-time long-distance relationship to keep me from having a "real" one. It didn't; as far as I was concerned, I already had a "real" relationship.

Trial Cohabitation

Still, both of us wanted to be together more. In the Fall of 1995, Andy saw an opportunity to give it a try. The massage therapy school offered a few classes in Grand Rapids, which meant that Andy could take some of them here, and the rest at their main campus. So two days each week he'd be in GR, and sleep at my place; the other nights he'd be "out east". It was a kind of trial living-together, and although it took some getting used to, it went well enough. Well enough that by December, Andy decided he wanted to take the plunge and move in for real. He'd get work with a local temp agency doing personal care work, and try starting a massage therapy practise in GR. It was everything he dreamed of: a real job and a real relationship. In retrospect I know I should have expressed my misgivings, but I didn't. What I really wanted was to try having us live in the same city for a while first: having him as a neighbour, not a roommate. But since he couldn't afford his own place, that suggestion would have killed the whole idea, and I couldn't do that to him. I wanted him to have a chance to make it all work.

It didn't. The professional aspect didn't go as well as he hoped. And the personal aspect was a disaster. The apartment was too small for both of us, and it was "mine" rather than "ours". I was used to living alone and had grown dependent on regular daily solitude to unwind and recharge. A couple days a week without it was no big problem, but suddenly without any evenings to myself, I just wound up and up and up. The workload at my job was stressing me out as well. And I wasn't ready to substitute for Andy's mother, whom he still depended on to either clean up after him or to nag him to do it himself. I was cranky and even bitchy, and he had no circle of friends or family in town to turn to for support. Neither of us was happy. We didn't even sleep in the same room anymore. Not a good sign.

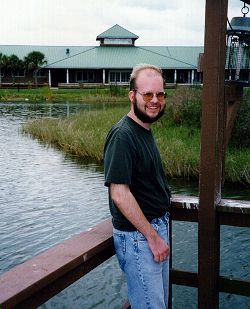

He came down with a bug of some kind (due to stress, no doubt), and went to K'zoo to see his old doctor. And stayed. (To be honest, I was relieved at first. I hoped we could return to "normal". We didn't.) He quit his job in GR, retrieved most of his stuff, and - having nothing better to do with himself - embarked on a bike trip for the summer. He rode from K'zoo to St. Simons Island, with extended stops along the way at the Short Mountain Sanctuary faerie commune in Tennessee, and at hostels in Atlanta and coastal Georgia. Among other things, he went to St. Simons for the chance to work on his relationship with his father and step-mother. After he got there, he decided to do the other thing he'd been considering: stay in the area for a while and look into attending nursing school in nearby Savannah. So he got his own apartment, and a job as a medical technician (doing blood work and other low-end skilled jobs) at the local hospital in Brunswick GA. Meanwhile, I went on a solo two-week backpacking trip in Northern Europe. We resumed phone calls and e-mails, though not as frequently as before. We both needed the space.

Trial Separation

Andy invited me to fly down to Brunswick for a long weekend in October 1996. We spent a day at Hostel in the Forest, where Andy had stayed for several days when he first arrived in the area, and it was like the best of our times together. He showed me around his new neighbourhood. And we talked about "us". Andy wanted to continue working on living independently, which I knew he needed. He had a decent start at it - thanks in no small part to the spiritual cleansing of his journey - and I was pleased to see how well he was doing. And he wanted me to have a life of my own as well in the meantime (or however long it turned out to be). So in the spirit of "if you love something, set it free", we agreed to be "ex-lovers" (and then made "ex-love" {smile}). We never closed the door on getting back together; we both wanted to when we were each ready. And even if that never came about, there was no changing the fact that we were still best friends. (And not in the clichéd sense of being "just friends.") Whenever I needed someone to talk to, Andy would be the one, and I would still be there for him.

When I got back to Michigan, I started thinking about finding a new apartment. My landlord had just raised the rent pretty substantially, and the apartment felt "tainted" by the conflict over our attempt to live together, so I wanted a fresh, larger place to start over... whether that would turn out to be with Andy later on, or even without him. I looked for a bigger place... one that would be big enough for both of us. And since I knew Andy well enough by that time to understand his tastes, I also chose a place that I knew he'd like as much as I did. In a sense, it was "ours".

He was feeling very lonely and isolated, even with family members nearby (in an e-mail message in mid-November, he moaned that he had no one to go see the upcoming Star Trek movie with), but he was determined to make it on his own. In that last e-mail message, he complained of a sinus infection. This might have been a misdiagnosed symptom of a cerebral aneurysm (the weakening of a blood vessel wall, which can cause headaches as it worsens). It's also possible that he really did have a sinus problem and was taking phenylpropanolamine for it. (PPA was a standard ingredient in over-the-counter decongestants at the time.) PPA has since been implicated as the cause of a small percentage of cerebral aneurysm bleeds and taken off the market. We'll probably never know whether this was a factor in Andy's case.

Everything Changes

22 November is best known as the date on which John Kennedy was assassinated. To me its significance is more personally painful. In the days before, Andy's aneurysm enlarged and began to bleed a little. When he didn't show up for work, and didn't answer his phone, his supervisor contacted his father, who found Andy semi-conscious in his apartment. Bill recognised that Andy needed serious medical care (Bill said Andy had also been vomiting), and got him to the hospital.

Upon returning home that Friday evening in 1996, after seeing that new Star Trek movie (by myself), there were phone messages from Andy's sister in Kalamazoo and from his step-mother's sister in GR, both relaying the news: He'd been diagnosed with a brain aneurysm, which would soon rupture and hemorrhage into the brain. Aneurysms don't always bleed, but if they do, unless fixed promptly by surgery, a hemorrhage in just about any part of the brain will result in death: it's 100% fatal. Depending on where in the brain it is, it can be relatively easy or difficult to fix. The surgery in Andy's case wouldn't be terribly difficult (as brain surgery goes), but it's often followed by severe complications, which the local hospital wasn't prepared to deal with. So they airlifted Andy to Emory University Hospital in Atlanta (on the far side of the state), where he finally had the surgery on 24 November. His mother immediately flew in from Michigan to be with him.

The next day, Andy was fairly lucid (for someone who'd just had his head opened). I'm told he asked about me. But then vasospasm struck. What happens in many aneurysm patients is that the blood vessels near the hemorrhage constrict, cutting off the flow of blood. Not only does this cause damage itself, by depriving that part of the brain of oxygen, it also increases the chances of a "regular" stroke, in which a clot closes off a blood vessel altogether. Andy's vasospasm was pretty severe, and they had to keep him in a drug-induced coma while they used various rather heroic treatments (a combination of medication and angioplasty) to keep the blood vessels open. There were times when it looked like he wouldn't make it. And they determined from CT ("cat") scans of the brain that he had in fact suffered a "minor" stroke in the anterior communicating artery of his left frontal lobe. It was about two weeks before it was safe to let him wake up. When I heard that he had, I told my boss that I was taking an open-ended vacation, and got on the first flight to Atlanta I could arrange. His father and step-mother were taken aback, thinking it was "too soon" for me to be visiting. As far as I was concerned, I'd already waited too long. I wasn't sure if I'd be allowed into Intensive Care (since I'm not "immediate family"). I didn't care. I simply had to be there for him.

The next day, Andy was fairly lucid (for someone who'd just had his head opened). I'm told he asked about me. But then vasospasm struck. What happens in many aneurysm patients is that the blood vessels near the hemorrhage constrict, cutting off the flow of blood. Not only does this cause damage itself, by depriving that part of the brain of oxygen, it also increases the chances of a "regular" stroke, in which a clot closes off a blood vessel altogether. Andy's vasospasm was pretty severe, and they had to keep him in a drug-induced coma while they used various rather heroic treatments (a combination of medication and angioplasty) to keep the blood vessels open. There were times when it looked like he wouldn't make it. And they determined from CT ("cat") scans of the brain that he had in fact suffered a "minor" stroke in the anterior communicating artery of his left frontal lobe. It was about two weeks before it was safe to let him wake up. When I heard that he had, I told my boss that I was taking an open-ended vacation, and got on the first flight to Atlanta I could arrange. His father and step-mother were taken aback, thinking it was "too soon" for me to be visiting. As far as I was concerned, I'd already waited too long. I wasn't sure if I'd be allowed into Intensive Care (since I'm not "immediate family"). I didn't care. I simply had to be there for him.

Coincidentally, I'd signed the lease for a new apartment the same day I got the first call about Andy's condition. I considered aborting the move, but remembered that in his last e-mail message, Andy had responded to my comments about the apartment I'd found with a single word: "MOVE!" So I went ahead with it. It was hellish - especially coinciding with the holiday season, and interrupted by going to Georgia - but it gave me something productive to focus on when I couldn't be with him, which probably saved my sanity. Even so, I pretty much sleep-walked through Thanksgiving and Christmas, and did no gift shopping at all... 'twasn't the season for me to be jolly.

Fortunately the Emory hospital staff didn't have a problem with letting me see him in the ICU; they figured out right away what our relationship was (even though we hadn't), and contrary to stereotypes about The South, they respected it even without comment. Andy's right leg was fully paralysed and his right arm was very weak; squeezing gently on an exercise ball was the best he could manage on that side. He was capable of only very rudimentary speech, and could not identify people by name. He was sometimes alert, but seemed thoroughly uncomprehending and incomprehensible. But most importantly, he was alive! So there was hope.

He gave no clear indication at first of recognising me (even though I'd started growing back the beard for him), and he had considerable trouble with his own name at times. He seemed like a twisted reflection of the man I loved, a helpless oversized infant, looking (with all the tubes and wires and "wrong" skin tone) like a half-machine Borg from that Star Trek movie. If I hadn't been so thrilled to actually see him again - alive - I would have been devastated. I barely slept that night, tossing and turning over and over like in a fever.

He gave no clear indication at first of recognising me (even though I'd started growing back the beard for him), and he had considerable trouble with his own name at times. He seemed like a twisted reflection of the man I loved, a helpless oversized infant, looking (with all the tubes and wires and "wrong" skin tone) like a half-machine Borg from that Star Trek movie. If I hadn't been so thrilled to actually see him again - alive - I would have been devastated. I barely slept that night, tossing and turning over and over like in a fever.

Over the following days and nights (most of which I spent in his ICU room, both with and without his mother Carol and step-mother Coby), his condition improved noticeably. His right arm got strong enough for him to start using it to mess with his various tubes and monitors (a mixed blessing, since he didn't understand what they were). He managed to move his right leg a little. His lungs started to clear up. His swallowing got good enough that he could start eating strained, puréed, and other liquid foods. His expressive aphasia (the inability to speak) began to subside gradually. A speech therapist was asking him to identify the objects she held by name, and he was getting most of them, but he came up with nothing when she showed him a sheet of paper. She prompted him, "A piece of..." "man's ass," he finished. At least we knew his sexual orientation hadn't been affected. {grin} He succeeded in remembering my name a few times. When I could get his attention without distractions and we both concentrated on it, he could carry on something loosely resembling a simple conversation, in which he seemed to demonstrate some vague awareness of his situation... at least that he was in a hospital and that something was seriously wrong. (The repeated, "oh god"s during one of our better "discussions" suggested this.) To our surprise, he was able to sing along smoothly with his father; this is because unlike talking, singing comes from the right side of the brain, which was uninjured. He moved out of intensive care a week after I got there. By then I had to return home, to finish moving and also return to work, figuring I needed to start rationing my vacation time for the long recovery ahead. (I didn't qualify for time off under the federal Family Medical Leave Act.)

Andy left Emory shortly after I returned to Michigan. His family drove him down to Jacksonville Florida, to one of the most-recommended neurological rehab facilities in the region. Bill and Coby took him out a week later. They didn't feel he was getting enough attention, and that the attention he did get was inconsiderate and even cruel. As they described it, when he wasn't with a family member or getting therapy (in other words, most of the time), he was restrained in bed, which wasn't doing him any good recovery-wise. They reported that one staff member insisted that Andy had to eat all of his meals with the rest of the brain trauma patients (some of whom were so severely impaired that they did little more than thrash about and wail, to the point that Andy was visibly frightened by them) "because he needs to learn to socialize with his own kind."

Andy left Emory shortly after I returned to Michigan. His family drove him down to Jacksonville Florida, to one of the most-recommended neurological rehab facilities in the region. Bill and Coby took him out a week later. They didn't feel he was getting enough attention, and that the attention he did get was inconsiderate and even cruel. As they described it, when he wasn't with a family member or getting therapy (in other words, most of the time), he was restrained in bed, which wasn't doing him any good recovery-wise. They reported that one staff member insisted that Andy had to eat all of his meals with the rest of the brain trauma patients (some of whom were so severely impaired that they did little more than thrash about and wail, to the point that Andy was visibly frightened by them) "because he needs to learn to socialize with his own kind."

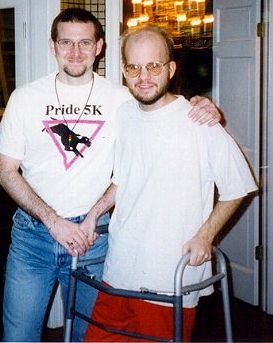

Reasoning that this environment was more of a warehouse than a place for Andy to grow and (re)learn, they took him to their home. In a more humane and nurturing environment where he could get the love and attention he needed (and despite my differences with the Georgia Bristols, I must say their home definitely qualifies as that), Andy's physical condition improved dramatically. Just a month after he awoke from his coma, he was walking with the aid of a walker and a person to help him balance.

A week after I'd finished moving, I flew back to Georgia early on New Year's morning. I spent the first six days of 1997 with him (using up a bit more of my vacation time), and was amazed by his progress. The grip strength of his right hand was up to 35lbs. (compared to 49lbs. for his left hand) so his strength was returning. Two weeks after I left, his step-mother reported that he was getting by without the walker altogether. All I could say about this is "Wow!" I've since learned that many stroke victims half-consciously give up on the use of their affected limbs, but since Andy didn't remember that his limbs weren't working, he kept trying to use them... which probably helped them to recover. He'd also regained most of the weight he'd lost following surgery. On 10 February he weighed 132lbs., up from around 115lbs. a couple months before. (He weighed about 145lbs. before he left on his bike trip south.)

A week after I'd finished moving, I flew back to Georgia early on New Year's morning. I spent the first six days of 1997 with him (using up a bit more of my vacation time), and was amazed by his progress. The grip strength of his right hand was up to 35lbs. (compared to 49lbs. for his left hand) so his strength was returning. Two weeks after I left, his step-mother reported that he was getting by without the walker altogether. All I could say about this is "Wow!" I've since learned that many stroke victims half-consciously give up on the use of their affected limbs, but since Andy didn't remember that his limbs weren't working, he kept trying to use them... which probably helped them to recover. He'd also regained most of the weight he'd lost following surgery. On 10 February he weighed 132lbs., up from around 115lbs. a couple months before. (He weighed about 145lbs. before he left on his bike trip south.)

By this time it started to become clearer what sort of damage had been done. He was conversational, and his lovably puckish personality was obviously intact. But he still had severe attention and retention problems. He couldn't focus on a task such as dressing himself; he'd get distracted or forget what he was doing, and walk off without his pants on or with only one shoe. He couldn't carry on much of a conversation without really concentrating, because he'd always forget what he'd just heard. His long-term memory was functional (he remembered all of his close friends and family), but it had large gaps and fuzzy areas. He had always been a bit spacy, so all of this wasn't completely "out of character" for him... it was just debilitatingly bad.

By this time it started to become clearer what sort of damage had been done. He was conversational, and his lovably puckish personality was obviously intact. But he still had severe attention and retention problems. He couldn't focus on a task such as dressing himself; he'd get distracted or forget what he was doing, and walk off without his pants on or with only one shoe. He couldn't carry on much of a conversation without really concentrating, because he'd always forget what he'd just heard. His long-term memory was functional (he remembered all of his close friends and family), but it had large gaps and fuzzy areas. He had always been a bit spacy, so all of this wasn't completely "out of character" for him... it was just debilitatingly bad.

His lack of short-term memory would remain as his most troubling disability . He couldn't reliably remember what year or month it was, and usually thought that he was in Michigan, not Georgia. He would even insist that St. Simons Island (where he was living) was in Michigan in order to justify this belief. When he was still unable to walk, he frequently tried to get out of his wheelchair, not remembering that he couldn't go anywhere. Michael (one of his best friends from Kalamazoo) visited, but when I talked to Andy on the phone a few minutes after Michael had left, he had forgotten all about it. Every time I talked to him (I called to talk to him frequently), I'd tell him about the new apartment; he'd usually - but not always - react with surprise. During one phone conversation (which wasn't going very well because he was distracted by the TV in front of him), I asked if I could talk to his father. Andy put down the cordless phone, saw that Dad was busy, looked up at the TV... and forgot I was there. I had to yell from "my" place on the sofa cushion to get his attention, so he'd pick up the phone again.

His lack of short-term memory would remain as his most troubling disability . He couldn't reliably remember what year or month it was, and usually thought that he was in Michigan, not Georgia. He would even insist that St. Simons Island (where he was living) was in Michigan in order to justify this belief. When he was still unable to walk, he frequently tried to get out of his wheelchair, not remembering that he couldn't go anywhere. Michael (one of his best friends from Kalamazoo) visited, but when I talked to Andy on the phone a few minutes after Michael had left, he had forgotten all about it. Every time I talked to him (I called to talk to him frequently), I'd tell him about the new apartment; he'd usually - but not always - react with surprise. During one phone conversation (which wasn't going very well because he was distracted by the TV in front of him), I asked if I could talk to his father. Andy put down the cordless phone, saw that Dad was busy, looked up at the TV... and forgot I was there. I had to yell from "my" place on the sofa cushion to get his attention, so he'd pick up the phone again.

Even without distractions, phone conversations were rather difficult, because the he'd only respond to me, not initiate. He wouldn't bring up new topics; he wouldn't ask me questions; he wouldn't (couldn't) tell me about what he'd done that day. (If asked, he'd often make things up, not to be deceptive, but because he understandably felt he should have an answer, so any stray memory or image would serve.) Whereas I previously had to fight sometimes to get a word in edgewise with him, it had become my job to carry the whole conversation, which I'm horrible at. But it was better than not talking to him at all, so I kept at it. At least I didn't need to worry overly much about finding things to talk about; if I had to, I could tell him the same stories every time. Repetition also increased the chances of my news sinking in.

An example of that came on a rare outing Andy and I went on together during my visit to St. Simons. Relieved to have a free "babysitter", the Bristols went out one night, and let me use one of their cars to take Andy into the business/tourist district of the island for the evening. We spent a while walking along the shore and so on. I did most of the talking, of course. For dinner we went to a restaurant Andy and I had been to once before (his brother's bachelor party a few years earlier). I had to order for him, since he couldn't pick something out and remember it to tell the waiter, but I know his tastes so he liked it. It was a fairly "normal" dinner out. (It helped that it was an "off" night at the restaurant, so it was much quieter than on our previous visit.) On the drive home, I quizzed Andy relentlessly: "Where did we have dinner?" "Um...." "It starts with an 'I'..." "Island Rock Cafe!" "That's right. So where did we have dinner?" I kept that up for the short drive home, and repeated it periodically after we got there. When the Bristols got home, I showed off our accomplishment: Andy remembered the answer.

It's fairly common for people with brain trauma similar to Andy's to lose awareness of their bladder and bowels. They simply can't tell whether they have to piss or take a dump. When I returned to Georgia in early February 1997, Andy was gradually regaining this ability. He would sometimes vanish suddenly from a room (causing some panic), only to be found in the bathroom, using the toilet. I was so proud! {grin} Thanks to a regular schedule of bathroom visits and reminders, we cut the number of accidents down. And he had a few dry nights as well before I left on 11 February.

Shortly before that visit, Andy's cognitive therapists conceded that they weren't really making much progress with him, because he'd continually forget whatever lessons they went over with him. He wasn't relearning anything. On top of that, Coby (his primary caregiver) was starting to reach the end of her already-highly-strung wits. She had to resort to nagging Andy to stay on task (fixing a sandwich, getting ready for bed), and he started getting snotty ("Yes, ma'am") in response to her tone. So a few days after I got down there, he went back to Emory for a week-long series of evaluations and tests at their Rehab Medicine facility, to see if there was anything further/different that could be done to help him redevelop his memory and concentration.

Shortly before that visit, Andy's cognitive therapists conceded that they weren't really making much progress with him, because he'd continually forget whatever lessons they went over with him. He wasn't relearning anything. On top of that, Coby (his primary caregiver) was starting to reach the end of her already-highly-strung wits. She had to resort to nagging Andy to stay on task (fixing a sandwich, getting ready for bed), and he started getting snotty ("Yes, ma'am") in response to her tone. So a few days after I got down there, he went back to Emory for a week-long series of evaluations and tests at their Rehab Medicine facility, to see if there was anything further/different that could be done to help him redevelop his memory and concentration.

I don't know what they determined. Unlike ICU visiting policies, patient confidentiality rules have the force of law. Since I'm not legally "family", the medical professionals didn't talk to me and wouldn't answer any of my questions... and Andy's step-mother would only give me her cut-and-dried interpretation of what she thought she understood about his condition. My observations or ideas were dismissed like those of a dim-witted child if they didn't match hers. And during my last stay at their house, she imperiously demanded that I get out of her house when I dared to criticise the way she habitually talked down to me. After all (she went on to explain) the only reason she allowed me to visit was to help her take care of Andy, and (being entirely new to the role of caregiver/babysitter) I wasn't doing a good enough job.

Anyway, I do know that Emory suggested he be admitted to a residential rehab facility. The goal was to get him more expert and intensive therapy to help him to at least become a little more self-sufficient. So his father and step-mother took him to the Florida Institute for Neurologic Rehabilitation, located in Wauchula FL, in the middle of nowhere, an hour or so east of Sarasota.

Anyway, I do know that Emory suggested he be admitted to a residential rehab facility. The goal was to get him more expert and intensive therapy to help him to at least become a little more self-sufficient. So his father and step-mother took him to the Florida Institute for Neurologic Rehabilitation, located in Wauchula FL, in the middle of nowhere, an hour or so east of Sarasota.

Not that anyone asked my opinion, but FINR seemed a fairly good program for him. For starters, it was in a beautiful rustic setting with lots of wild birds, small mammals, and the occasional small 'gator. This suited Andy's tastes well. They generally kept him busier than when he was living with his step-mother and father, and offered him more challenges to deal with. (He didn't seem to get enough exercise, however; he'd gotten a little flabby again when I visited in April, after losing a lot of weight during his recovery.) One thing I liked was that the people there would direct their questions to Andy (not whomever was with him), because even with diminished cognitive capacity, Andy's opinions and desires should still be given precedence (within reason, of course). In particular, I hoped that when it came time to decide where he was going to live semi-permanently, he would get to make that choice. His parents don't know him (or recognise the depth of our relationship) well enough to make those decisions for him. (And I know that he'd chose to live in West Michigan... and with me, if given the option.) It didn't work out that way, though.

Not that anyone asked my opinion, but FINR seemed a fairly good program for him. For starters, it was in a beautiful rustic setting with lots of wild birds, small mammals, and the occasional small 'gator. This suited Andy's tastes well. They generally kept him busier than when he was living with his step-mother and father, and offered him more challenges to deal with. (He didn't seem to get enough exercise, however; he'd gotten a little flabby again when I visited in April, after losing a lot of weight during his recovery.) One thing I liked was that the people there would direct their questions to Andy (not whomever was with him), because even with diminished cognitive capacity, Andy's opinions and desires should still be given precedence (within reason, of course). In particular, I hoped that when it came time to decide where he was going to live semi-permanently, he would get to make that choice. His parents don't know him (or recognise the depth of our relationship) well enough to make those decisions for him. (And I know that he'd chose to live in West Michigan... and with me, if given the option.) It didn't work out that way, though.

When I visited him at FINR in mid April 1997, he seemed to be focusing a little better on personal care tasks. He might still need to be reminded to put his shoes on, but he'd usually get them on without getting distracted and forgetting what he was doing. It's not much, but we take what we get.

Most of the time, when asked for the current month and year, he answered correctly. It was a frequent quiz he received, which helped him remember. He also knew (usually) what the name of the facility was. This suggests that he was getting some sense of time and place and could form some new memories. One "feat" from that time period was when I made a comment about my strained finances, and he referred to the cost of "the new apartment". He'd lost all memory of the weeks preceding his stroke, so he didn't remember it from our pre-stroke conversations. So the only way he knew about it was from me mentioning it (repeatedly) in the months since then. As another example from a phone conversation several months later, he didn't remember (after I'd told him a dozen times previously) that I'd gone back to school, but when I followed up by asking if he knew the name of the school, he remembered it... despite the fact that he'd probably never even heard of the school before the stroke (and even if he had, it's definitely not the school he would've guessed I was at). This means that he's capable of learning some new information, so he isn't doomed to spend the rest of his life as if it were still 1996. With some effort, he may be able to keep up with the rest of the world... somewhat.

Most of the time, when asked for the current month and year, he answered correctly. It was a frequent quiz he received, which helped him remember. He also knew (usually) what the name of the facility was. This suggests that he was getting some sense of time and place and could form some new memories. One "feat" from that time period was when I made a comment about my strained finances, and he referred to the cost of "the new apartment". He'd lost all memory of the weeks preceding his stroke, so he didn't remember it from our pre-stroke conversations. So the only way he knew about it was from me mentioning it (repeatedly) in the months since then. As another example from a phone conversation several months later, he didn't remember (after I'd told him a dozen times previously) that I'd gone back to school, but when I followed up by asking if he knew the name of the school, he remembered it... despite the fact that he'd probably never even heard of the school before the stroke (and even if he had, it's definitely not the school he would've guessed I was at). This means that he's capable of learning some new information, so he isn't doomed to spend the rest of his life as if it were still 1996. With some effort, he may be able to keep up with the rest of the world... somewhat.

I wish there were more I could do for him. If I could, I'd take him back home to live with me, but he really needs someone to keep an eye on him whenever he's not asleep, and I can't do that and make enough money to support myself (let alone him as well). So I've been forced to leave him with his step-mother (who dislikes and annoys me as only a step-mother-in-law could) and father (who habitually defers to his wife). Not that I have much choice. Andy granted his father durable power of attorney just before the surgery, so Dr. Bristol (or rather, his wife) calls the shots. Because the disability is permanent, Bill is presumably Andy's legal guardian by now. And since I said some things that greatly offended his wife (pretty much the same things you've been reading, though perhaps a bit less diplomatically), he now refuses to let me see Andy. (They probably assume I was bad-mouthing them to Andy; in fact, I had consistently defended them whenever Andy expressed his own negative opinions of them.) I didn't know it at the time, but that trip to FINR in April 1997 turned out to be the last time I've seen him.

I continued talking to Andy frequently on the phone while he was still at FINR and the nursing facility he went to immediately afterward. But he couldn't stay at FINR indefinitely, and there just aren't many options his limited insurance will pay for and which would work out for him. Nursing homes - the usual place for people with his medical needs - just aren't prepared to deal with an opinionated queer 30-something able-bodied man who gets confused and acts up at times. For a short period he was living in some kind of group home, which apparently wasn't working out very well either. It was tough to hold onto hope and to try to mantain a relationship of sorts with him (especially with my job situation "in flux"), but I called a few times a month, whenever I could manage the time and emotional strength.

Then one day in late 1997 when I called the home to talk to him, I was told he wasn't there anymore. They said he'd moved back in with his father and step-mother. Bill and Coby wouldn't accept phone calls from me. So I waited. The next year, the Georgia Bristols and Andy came to Kalamazoo for a family gathering (someone's birthday, I believe). Andy spent some of that time with his mother, and Carol called and arranged for me to spend a few hours with him at her house, at a time when his father and step-mother would be elsewhere and wouldn't have to see me. But when Bill heard about it, he vetoed it, saying that Andy didn't need to have old romantic feelings stirred up, or something along those lines. Andy's mother and sister argued rather emphatically on behalf of my visit, but Bill didn't budge. I considered just going to Kalamazoo and watching for him from a distance, but decided it would be too painful (as well as inflammatory if I were seen). So I was officially excluded from Andy's life. Aside from sending him a book of Matt Groening cartoons for his 30th birthday in June 1999 (there was no reply), I haven't had any contact with him since the routine phone call that turned out to be my last. So I never even got to say "goodbye"... which I supposed is for the best, since I wouldn't have been able to.

I could try to fight this, but I figure there's little point. For one thing, I don't have any legal standing from which to argue; I'm just "a friend". His mother and sister would probably try further on my behalf if I asked them to, but they don't deserve to get stuck in the middle of a conflict like this; they've been through far too much already, and I'm too fond of them to put them through any more. I also respect how much his father and step-mother have done and what they're going through. They've made incredible sacrifices for Andy, and whether or not I agree with every aspect of how they're doing it, I owe them a great deal for that. They'll probably do a better job of caring for him without the stress of also having to interact with someone they apparently hate. I do think Andy would be happier if I were a part of his life, but he doesn't consciously realise that I'm not around (for all he knows, he might have seen me yesterday)... so I figure - or at least hope - that my absence isn't hurting him. So... the family all benefit, Andy doesn't suffer, and only I lose out. "The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the one."

I could try to fight this, but I figure there's little point. For one thing, I don't have any legal standing from which to argue; I'm just "a friend". His mother and sister would probably try further on my behalf if I asked them to, but they don't deserve to get stuck in the middle of a conflict like this; they've been through far too much already, and I'm too fond of them to put them through any more. I also respect how much his father and step-mother have done and what they're going through. They've made incredible sacrifices for Andy, and whether or not I agree with every aspect of how they're doing it, I owe them a great deal for that. They'll probably do a better job of caring for him without the stress of also having to interact with someone they apparently hate. I do think Andy would be happier if I were a part of his life, but he doesn't consciously realise that I'm not around (for all he knows, he might have seen me yesterday)... so I figure - or at least hope - that my absence isn't hurting him. So... the family all benefit, Andy doesn't suffer, and only I lose out. "The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the one."

He's a thousand miles away from me, but it might as well be a thousand light-years. I miss him profoundly. After all these years, I don't consciously think about him as often as I used to, but I feel his absence every day, like there's a hole in my life. It's like he's died... but with the cruelly tenuous hope of his "resurrection" someday through a medical breakthrough. (Stem cell research holds great promise at restoring lost neurons, and because of his relative youth and potential for benefit, Andy would be a good candidate for such a treatment, but - for both political and medical reasons - it won't happen any time soon.) I don't suppose I'll ever give up all hope - and if anyone in the family reads this, I would like to know how Andy is doing - but it doesn't look like he and I will ever be together again... something I'm coming to accept.

There's no need for sadness

There's no need for sadnessNo time for regret Though we can't be lovers We can still duet And since we're not together We'll never have to part I'll always have a song for you A song for you in my heart lyrics from "A Song In My Heart" © 1992 Ron Romanovsky, from his album Hopeful Romantic |

Aneurysm Info

A few weeks after Andy's bleed, I wrote a narrative about what happened for Bill Maple's Aneurysm Support site, an award-winning labor of love which includes essays by aneurysm survivors, their loved ones, and those who have lost people they love to aneurysms. My essay about Andy - the kernel from which this page grew - is in the list of Brain Aneurysm narratives. It's labeled "My Best Friend" with my name, dated 18 Dec 96 (or you can jump to it directly). I recommend reading at least a selection of these essays to get an idea of the many varied ways that brain aneurysms can affect people.